Senior diplomats have gathered to talk about peace in Afghanistan dozens of times through the years, and the Taliban have uniformly been both absent and dismissive of their efforts.

Publish dateWednesday 28 March 2018 - 09:14

Story Code : 160750

AVA- On Tuesday, Afghanistan and its allies, neighbors and benefactors gathered in Uzbekistan’s capital to talk again. The Taliban were, to be sure, absent as usual, but they have kept a studious public silence about this latest effort to negotiate peace.

The difference this time, many of the delegates said at an unusually optimistic conference, was a sweeping offer from the Afghan government on Feb. 28 to lure the Taliban to the table, along with increased international pressure. Even among the feuding factions within the Afghan delegation, there has been remarkable cohesion over the latest peace overture.

Beyond even the Taliban’s rare refusal to dismiss the offer out of hand, there is evidence that a more serious conversation is underway among the insurgents.

Reached for comment, several senior Taliban officials acknowledged this week that the movement was busy in internal discussions over how to respond to the government’s offer. The Taliban members, as well as Afghan and Western officials, said that diplomatic visits with Taliban political representatives, in Qatar and elsewhere, had increased in recent weeks to try to persuade the insurgents to come to talks.

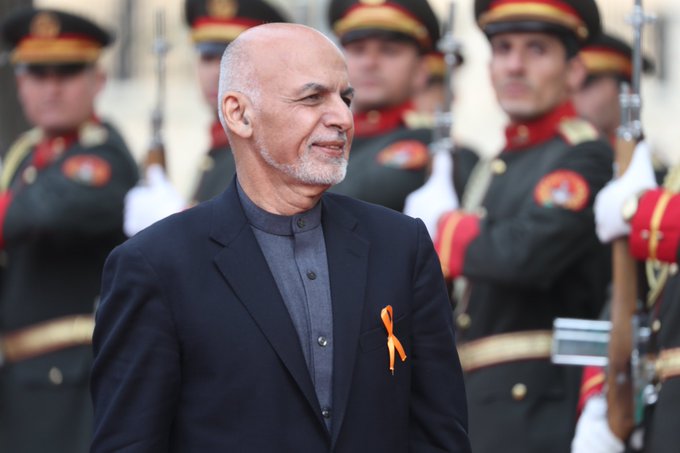

The offer on the table, made by President Ashraf Ghani, included recognition of the Taliban as a legitimate political party, passports for their officials, an office in Kabul or somewhere else they preferred, the release of Taliban prisoners and efforts to remove their leaders from international sanctions lists.

Just because the Taliban may be discussing the offer does not mean they’re going to take it, of course. Most of the Taliban figures reached for comment by The New York Times preferred to remain quiet, referring the queries to representatives in Qatar. Members at the office in Qatar, in return, did not respond to requests for comment.

Some Taliban figures who did speak made sure to express their old mistrust of any peace offer by the Western-backed Afghan government.

Mullah Hamidee, a Taliban military commander in the south, said: “Our stance on peace talk is totally dependent on foreign troops’ abandoning our country. Anytime they set the date for leaving, we will be willing to talk on peace.”

One senior Taliban commander, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was talking to the news media without the leadership’s permission, insisted that the insurgents were not ready to negotiate directly with the Afghan government. The discussions underway, he said, are over what kind of negotiations might be acceptable, “but the mood of leadership is likely to not initiate peace talks with the Afghan government.”

While that is far from a rousing endorsement, it is a long way from the Taliban’s outright and fulsome dismissal of past peace initiatives, always insisting that they would talk only to the “occupiers,” meaning the American military, as long as they remained on Afghan soil.

Recently, several former officials involved in previous efforts to negotiate with the Taliban said the United States would need to play larger role as facilitator if the insurgents were to take any prospects of negotiations seriously.

One senior diplomat in Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital, said the government’s offer had been a game changer.

“The Taliban feel a bit confused, they feel pressured,” he said. “At the Kabul conference, everybody said they should talk to the Afghan government; they are the only ones insisting they should talk to the occupiers.”

As the government of Uzbekistan convened the conference here, pressure on the Taliban came from another, unexpected quarter: the group’s own heartland.

In Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand Province, a major Taliban stronghold, a suicide bombing at a wrestling match Friday killed 14 people. This week hundreds of Helmand residents held a sit-in, vowing to carry out a “long march” to the Taliban-held town of Musa Qala to demand peace talks. The protesters included women, rarely seen outside their homes in that conservative corner of Afghanistan.

“The only aim of the sit-in is to stop fighting from both sides,” said one of the organizers, Iqbal Khaibar. “The Taliban should not send bombers and the government should not drop bombs on them.”

He said their march would take place without security: “This is our country and we can go anywhere in it.”

Akram Khpalwak, the head of the Afghan government’s High Peace Council secretariat, was among the optimists. “The narrative needed to change,” he said. “There was a perception that, over the years, the Taliban wanted peace but the government side did not have a clear plan for it, and was not offering a comprehensive plan. We wanted to change that perception, and make an offer that leaves few questions.”

The difference this time, many of the delegates said at an unusually optimistic conference, was a sweeping offer from the Afghan government on Feb. 28 to lure the Taliban to the table, along with increased international pressure. Even among the feuding factions within the Afghan delegation, there has been remarkable cohesion over the latest peace overture.

Beyond even the Taliban’s rare refusal to dismiss the offer out of hand, there is evidence that a more serious conversation is underway among the insurgents.

Reached for comment, several senior Taliban officials acknowledged this week that the movement was busy in internal discussions over how to respond to the government’s offer. The Taliban members, as well as Afghan and Western officials, said that diplomatic visits with Taliban political representatives, in Qatar and elsewhere, had increased in recent weeks to try to persuade the insurgents to come to talks.

The offer on the table, made by President Ashraf Ghani, included recognition of the Taliban as a legitimate political party, passports for their officials, an office in Kabul or somewhere else they preferred, the release of Taliban prisoners and efforts to remove their leaders from international sanctions lists.

Just because the Taliban may be discussing the offer does not mean they’re going to take it, of course. Most of the Taliban figures reached for comment by The New York Times preferred to remain quiet, referring the queries to representatives in Qatar. Members at the office in Qatar, in return, did not respond to requests for comment.

Some Taliban figures who did speak made sure to express their old mistrust of any peace offer by the Western-backed Afghan government.

Mullah Hamidee, a Taliban military commander in the south, said: “Our stance on peace talk is totally dependent on foreign troops’ abandoning our country. Anytime they set the date for leaving, we will be willing to talk on peace.”

One senior Taliban commander, who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was talking to the news media without the leadership’s permission, insisted that the insurgents were not ready to negotiate directly with the Afghan government. The discussions underway, he said, are over what kind of negotiations might be acceptable, “but the mood of leadership is likely to not initiate peace talks with the Afghan government.”

While that is far from a rousing endorsement, it is a long way from the Taliban’s outright and fulsome dismissal of past peace initiatives, always insisting that they would talk only to the “occupiers,” meaning the American military, as long as they remained on Afghan soil.

Recently, several former officials involved in previous efforts to negotiate with the Taliban said the United States would need to play larger role as facilitator if the insurgents were to take any prospects of negotiations seriously.

One senior diplomat in Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital, said the government’s offer had been a game changer.

“The Taliban feel a bit confused, they feel pressured,” he said. “At the Kabul conference, everybody said they should talk to the Afghan government; they are the only ones insisting they should talk to the occupiers.”

As the government of Uzbekistan convened the conference here, pressure on the Taliban came from another, unexpected quarter: the group’s own heartland.

In Lashkar Gah, the capital of Helmand Province, a major Taliban stronghold, a suicide bombing at a wrestling match Friday killed 14 people. This week hundreds of Helmand residents held a sit-in, vowing to carry out a “long march” to the Taliban-held town of Musa Qala to demand peace talks. The protesters included women, rarely seen outside their homes in that conservative corner of Afghanistan.

“The only aim of the sit-in is to stop fighting from both sides,” said one of the organizers, Iqbal Khaibar. “The Taliban should not send bombers and the government should not drop bombs on them.”

He said their march would take place without security: “This is our country and we can go anywhere in it.”

Akram Khpalwak, the head of the Afghan government’s High Peace Council secretariat, was among the optimists. “The narrative needed to change,” he said. “There was a perception that, over the years, the Taliban wanted peace but the government side did not have a clear plan for it, and was not offering a comprehensive plan. We wanted to change that perception, and make an offer that leaves few questions.”

Source : خبرگزاری Afghan Voice Agency(AVA)

avapress.com/vdciwuazut1aqy2.ilct.html

Top hits